There’s more than one way to build a four cylinder motor, but few configurations come with the same depth of virtues as the exotic V4.

It’s an exciting time in the motorcycling world, with seemingly endless innovations headed our way from every manufacturer and their dog. Ducati in particular, famed for pioneering technology such as Desmodronic valves systems and bringing monocoque chassis designs to the forefront of production sportsbikes, have more than done their fair bit to make our biking world better, so we can forgive them for not seeing the virtues of the V4 motor. Well, at least in a street bike context, as they’d seen the light several years back in their MotoGP efforts – the inaugurator for much of the tech that’s made the new Stradale motor the performer that it is. But before digress any more about Ducati’s new choice of configuration, let’s take a more general look at the brilliant V4.

In the Beginning

The first V4s were designed and manufactured by a Parisian bloke who went by the name of Emile Mors, but he only used them in cars. Weird-o! It wasn’t until the 1930s when Matchless started to use them in models like the Silver Hawk, that they were considered suitable for bikes. Fast forward 50 years though, and although there had been a spattering of V4 motorcycles in the meantime, the 1980s was the golden era of sexy new two-stroke and four-stroke V4 bikes such as the Suzuki RGV 500, Honda VF1000R and the Yamaha V-Max, to name but a few.

Since the ‘80s there have been a real smorgasbord of V4s hitting the racetracks and the roads, many of which have captured the hearts of motorcyclists the world over. And it’s easy to see the draw, with an arguably perfect balance of torque and peak power, not to mention the completely unique sound, what’s not to like? Well it’s a fact that there has been some jolly impressive motorbikes utilising V4 engines, but if they are so good why isn’t everyone using them?

Most Desirable Aprilia RSV4

We aren’t privy to all the manufacturers sales figures here at Fast Bikes (in fact nobody tells me anything) but I can only imagine that after Aprilia’s RSV4 came home with our coveted SPOTY trophy last year, their sales figures will have gone through the roof. And deservedly so. With a big fat tick in all the boxes electronically speaking, full Öhlins bouncy bits and a tested power haul of 180bhp, on paper the RSV4 is a class act, but on tarmac it’s an even classier one. Some people will always turn their nose up at Italian exotica like this, questioning its reliability, but the lifetime warranty that Aprilia are offering just proves how confident the I-ties are with their new machine.

The technical bit

It’s true that, as well as the orgasm inducing noise, there are some real advantages that this technology provides in the performance department. For starters, there is a beneficial lack of ‘inertial torque’. In simple-ish terms, this is the turning force applied to the crankshaft due to the mass of a ‘slowing down’ piston acting against the accelerating mass of a ‘speeding up’ piston. When these two (effectively) opposite forces are applied to the crankshaft in different places, it creates a large turning force.

Think of it as the pistons giving the crank a Chinese burn. Because in a V4 opposite pistons are linked to the crank at the same point, they don’t try and twist anything, they just work together to turn the crank. Not only does this give the rider a much better feel for the tarmac, it gives the rear tyre, and indeed the entire drivetrain, an easier time because all the ‘pulses’ from the engine are acting in the same direction. This is a feature that many manufacturers have successfully emulated using crossplane cranks (Yamaha R1, for instance) in inline-fours; a crank with 90° between crankpins alleviates this ‘inertial torque’ in exactly the same way.

Another way that the crossplane crank engine emulates the V4 is in its firing order. A conventional inline four fires every half a rotation of the crank (every 180°). A V4, on the other hand, has an uneven firing order, typically having a 270° pause between the fourth and then the first cylinder firing (so, once every two turns of the crank). The theory is that this pause gives the tyre time to ‘relax’ back to its original position and key into the road surface, offering the rider greater levels of traction when really getting the hammer down.

Good things… small packages

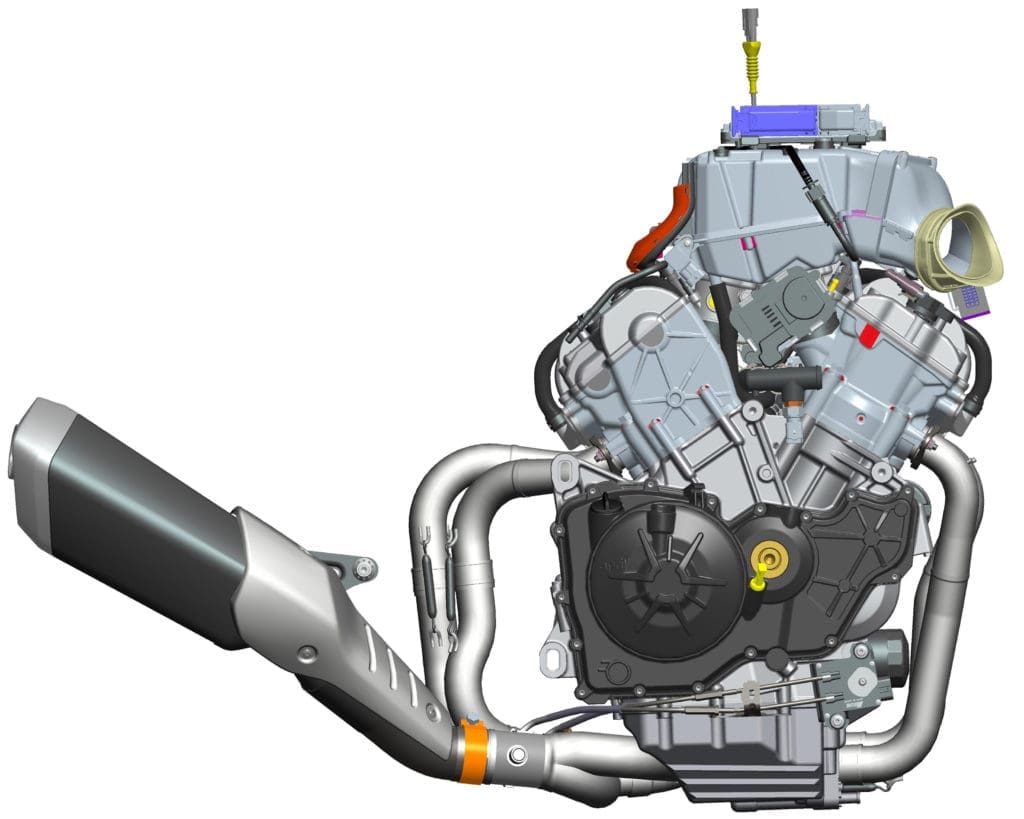

One quality of the V4 engine that the crossplane crank jobbies can’t mimic is its size. Because, in a V4, two pistons can be connected to the crank at the same place, the crankshaft can be shorter. So the shorter crank means a more compact engine, right? Well yes and no. It means the engine, and therefore the bike, can be narrower, giving the bike a tighter feel and allowing ridiculous amounts of lean angle.

But the front to rear dimension is massive compared to an inline-four which can often command a long wheel base; not always great in a sportsbike. In the case of the RSV4, Aprilia have tightened the V angle to 65° try and alleviate this, and in doing so have created one of the best handling bikes available. But tightening up the V-angle is not without its disadvantages.

An important consideration during the design stage of a V4 bike engine is the possibility of overheating rear cylinders, due to a reduced amount of airflow. A tighter V-angle means even less airflow resulting in hotter still rear cylinders. It also means you need very small hands if you ever decide to do any work in or around your engine. It can be a very tight affair, even before you try and squeeze two banks of inlet systems between the cylinders. Despite the many and varied qualities of the V4 engine, they don’t come without a faux pas or two. With complicated (therefore expensive) designs (i.e. exhausts) and double the ancillaries (i.e. cylinder heads and cams), to date V4 motors are still the reserve of the relatively high end motorcycle. Some may say that Yamaha et al have hit the nail on the head with the best of both worlds crossplane crank inline four, whilst others would argue that’s merely a half measure.

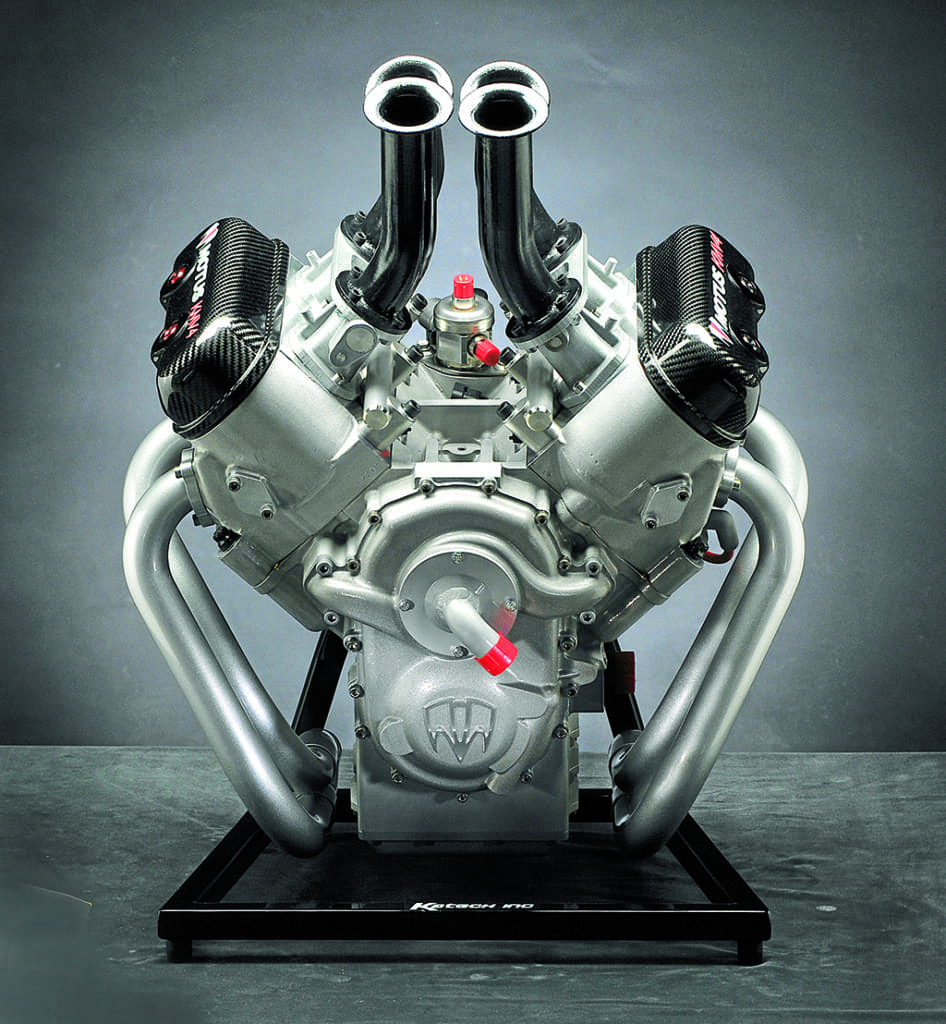

Most Expensive Honda RCV213V-S

At £137,000 you’d probably struggle to buy one of these without the wife finding out, especially when you consider it’ll cost you another £10k for the Sports Kit which plumps the standard 159bhp up to a more value for money 216bhp. You get Moto GP derived engine and electronics technology as well as GP style mass centralisation. A cleverly designed frame affords rigidity only where it’s needed without piling the pounds on resulting in a 160kg dry weight; that’s British Supersports territory. It’s all very well though having a ‘Moto GP’ bike in your garage, you would certainly be the talk of the town, but at not far off ten times the price of a standard Fireblade, how many seconds do you think it would really knock off your lap times?

So what’s next?

Have we really had the golden era of the V4 motorcycle? It’s easy to see why the major Japanese manufacturers steered away from V4s over the last two decades because they are complicated and so expensive to manufacture. But will Japan reach the limit of inline four-pot technology as Ducati admitted to have done with the L-twin?

Will we see more V4 motors making their way into genuine production sportsbikes, or is it just a fringe movement that will never catch on? Well, when you look at the final 2017 MotoGP standings and see that three of the top four bikes were powered by V4s, it’s a technology that is hard to ignore. A technology that I look forward to seeing a lot more of in the years to come.

Most Nostalgic – Honda RC30/45

If I said the RC30 sparked more nostalgia than the RC45, fans of the ’45 would poke me in the eye, and vice versa. Developed for HRC’s assault on the newly formed World Superbike Championship, the VFR750R RC30 was as trick as trick got back then. Titanium con-rods, gear driven cams, close ratio box, slipper clutch and Showa forks all helped Fred Merkel win the inaugural World Superbike Championship in 1988. By 1994, the ’30 was getting a bit old in the tooth so Honda released an updated RVF750 RC45. Another ‘homologation special’ the revvier, fuel injected, more race focused ’45 enjoyed championship wins all throughout motorcycle racing in the mid to late ‘90s. You might call the RC45 the ultimate ‘90s race bike, but without the trail blazing RC30 it probably would never have existed.

Want more Fast Bikes? Subscribe from just £10